Based on the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, literature supporting long-term opioid therapy for pain is limited; in fact, research shows increased risk for harm with long-term opioid use. Benefit for starting new patients on long-term opioid therapy should be individualized to the patient and the disease process with careful consideration of the risks and benefits. Patients already on opioids should consider reducing to lower and safer doses in collaboration with their provider after consideration of their risks. Many patients already on opioids may require no adjustment if risks are managed and functional improvement is sustained. The CDC Guidelines are not to be applied to many populations, such as to those with cancer or following major surgery, and harm can be done when such guidelines are inappropriately applied.

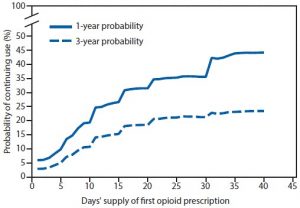

A recent report noted that in a representative sample of ~1.3 million opioid naïve, cancer-free adults who received at least a 1-day prescription for opioid pain relievers, the likelihood of chronic opioid use increased with each additional day of medication supplied starting with the third day and risk of use at 1-year doubled with a 5-day prescription.

The sharpest increases in chronic opioid use observed:

- after the 5th and 31st day on therapy (see figure)

- if a patient received a second opioid prescription

- an initial 10- or 30-day supply was given

- if the prescription was over 700 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) (e.g. oxycodone 10mg PO q6h PRN pain x 14 days = 840 MME).

The highest probability of continued opioid use at 1 and 3 years was observed among patients who started on a long-acting opioid. Of note, in this large population, approximately 70% of patients had an initial duration of opioids of ≤7 days, but 7.3% were initially prescribed opioids for ≥31 days.

The rates are not as high after surgery, but a recent report notes that approximately 5-7% of opioid-naïve patients undergoing major or minor surgery will become persistent opioid users (continued use >3 months from surgery).

Long-acting opioids increase the risk of unintentional overdose deaths but also may increase mortality from cardiorespiratory and other causes. A recent study describing this was performed in Tennessee (see references).

In summary, for cancer-free, previously opioid-naïve medical patients receiving a 10-day supply of opioids, approximately 20% are still using opioids after 1 year, and for patients receiving a 30-day supply as their initial opioid prescription, approximately 35% are still using opioids after 1 year. These rates are approximately 5-7% for surgical patients. Thus, care should be taken to a) maximize use of scheduled non-opioid analgesics and b) use opioids for the shortest duration possible while optimizing function.

Naloxone

Co-prescribing naloxone to individuals at increased risk for respiratory depression is an accepted and recommended practice. Research has shown this practice may also reduce emergency department visits for opioid-related adverse events among patients taking opioids for chronic pain.

Naloxone training materials for the public

References:

- Hayhurst CJ, Durieux ME. Differential Opioid Tolerance and Opioid-induced Hyperalgesia: A Clinical Reality. Anesthesiology, 2016, Vol.124, 483-488

- Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician, 2008 Mar;11(2 Suppl): S105-20

- Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of Initial Prescription Episodes and Likelihood of Long-Term Opioid Use — United States, 2006–2015. MMWR 2017 Mar 17; 66(10):265-269

- Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Prescription of Long-Acting Opioids and Mortality in Patients with Chronic Noncancer Pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2419

- Behar E, MS, Bagnulo R, Coffin PO. Acceptability and Feasibility of Naloxone Prescribing in Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Prev Med. 2018 Sep; 114: 79–87

- Coffin PO, Behar E, Rowe C, et al. Nonrandomized Intervention Study of Naloxone Coprescription for Primary Care Patients Receiving Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(4):245-252

- Dahan A, Aarts L, Smith TW. Incidence, Reversal, and Prevention of Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression. Anesthesiology, 2010 Jan;112(1):226-38.